The golden rules of TV sitcom writing that will make your pilot stand out from the crowd.

I’m going to assume that if you’re reading this, you’re a writer. You know how to write, you’ve probably written several screenplays or teleplays, and maybe they’re not selling. That or you’re working towards selling your first script and you’re doing some homework before taking the step towards submitting your work. You’ve put in an incredible amount of effort getting to this point. Years of honing your craft, and weeks if not months on the script. Now I, or someone like me, is statistically going to call your baby ugly. Here’s what you can do to turn that rejection into an offer.

Please be aware that most of this is only applicable to sitcom writing specifically, as some of the elements below go against the grain of classic writing theory.

I’m not going to assume your writing level, competency or prior successes, so I’m going to start with the obvious ones and then I’ll aim for the gold near the end, if you’re still with me.

1. Characters

It’s all about the characters. We don’t laugh at locations or props; we laugh at people. Why do we laugh at people? Because they are relatable and flawed.

We laugh because we identify with certain traits in the show’s characters, and then feel satisfaction in the fact that they are doing worse than us, or messing things up in some way. We need to feel better than the characters, and their faults and failures make us feel better about ourselves.

The more we can relate, the more we connect and ultimately the more we can laugh at how we see ourselves as better than them.

2. Funny

I know this sounds painfully obvious, but you’d be horrified if you knew how much it really needs pointing out. Your story has to be funny. I appreciate that what constitutes as funny can vary. There are different types of sense of humour, but you hopefully will have done your homework and you understand the demographic that your show is aimed at and you’re writing your humour for that specific audience.

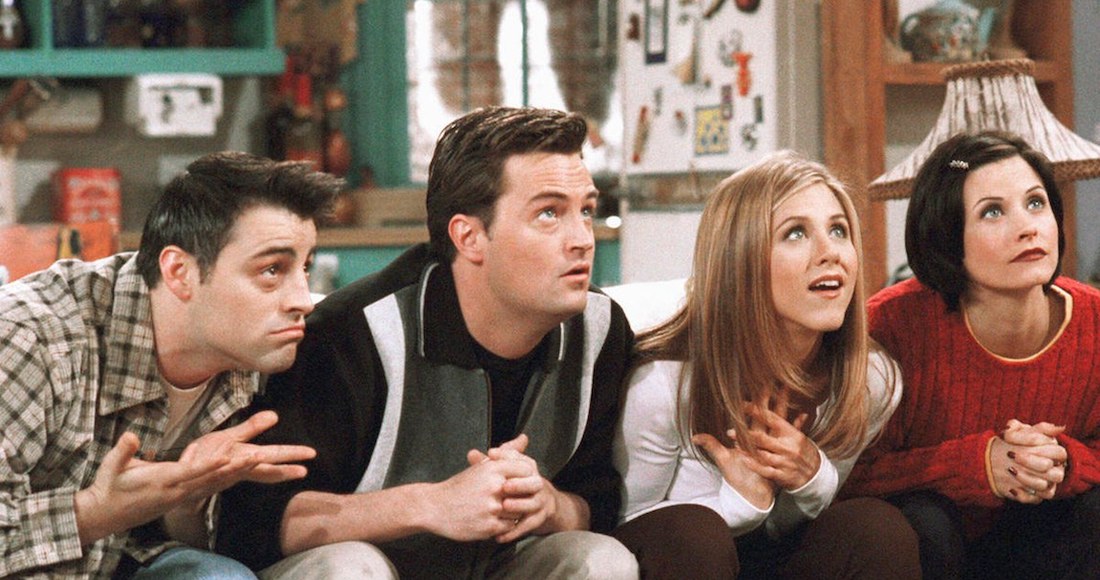

Whether it’s Niles and his bungling every time he sees Daphne in Frasier, or Sheldon’s naivety despite his brilliance in The Big Bang Theory, or even the witty one-liners coming from Chandler in Friends. Find the comedic personality of each of your characters, and weave that into your show. One personality and a collection of drones receiving punchlines is unlikely to cut it. If each character is also funny in their own way, you will also have a broader appeal.

3. Production Cost vs Value

You may not want to put a price on art, but someone like me will, and the channels definitely will. Most channels have a rate card for what they are prepared to pay per episode of a show; certainly, a new show without 8 seasons behind it. They will want to risk assess the viability of consistently making that show for that money based on the viewers (and ultimately the advertising) that the show’s potential audience will attract. They are running those numbers in their heads as they are reading your first page. Be aware of this.

We established that the key to comedy is in the characters. So, unless you absolutely have to set your comedy show on the moon, with all the expensive VFX that goes with it, don’t. A safe bet is a here-and-now comedy that is low on big budget departments, like VFX.

4. Keep to the Specification

Many channels will be quite specific about the types of comedies that they are currently looking to commission. Similarly, production companies that are hoping to fill those slots will reflect that need. Your animated comedy about cavemen, aimed at young teenagers, will never sell if the commissioning editors are looking to fill a 10pm slot on their channel that is targeting a 30-something audience.

If you have that script already written, that’s great. There will be a place for it at some point and somewhere. Don’t burn bridges in the meantime though by sending it in the hope that the production company or the channel will see your genius and flex on their requirements. Nothing good will come from this. Write something fresh with the specification in mind, rewrite the story to the tone and style required, or wait for the right time for the story you already have. Those are pretty much the only choices you have that won’t work against you.

5. Reflect the Pace of the Show

This is the one that most miss. There may be other points missed too, but I guarantee that 90% of all submissions received from new writers will fall into this one.

The pilot, or first episode of a series, is supposed to set the pace and tone for the show, and it is your show’s advert to the channel and its audience. It needs to be a true reflection of what the rest of your show is going to be like. This is a tricky one for many people as they are trained to deliver exposition to bring the audience up to speed. Furthermore, they are trained to have something exciting happen to hook an audience. What better than to kill two birds with one stone by writing an exciting expository series opener, right? There’s nothing wrong with exciting things going on, but this cannot be disproportionate to the rest of the episodes in the series.

Commissioners will want repeatability in a format. New audience members come along at varying stages of the release of a show and if an audience member cannot understand what is going on without watching the first episode then it’s a non-starter for the channel. People are smart and they will catch up on character dynamics that have been missed, but I’m talking about big expositional pieces that leave an audience completely lost if they’ve missed it.

If your show has an opening episode that sets the scene for the rest of the show, then you need to take a look at the rest of the series and ask yourself this question: Can my audience jump in on Episode 2 and survive? If the answer is Yes, then dump episode 1 altogether. Your new episode 1 was your old episode 2, and now you have a sellable pilot. If the answer is No, then you have a bigger problem and you need to rethink your whole idea.

In Summary

Get The Inside Track

Hear first about casting calls, writing script submission requests, and much more.